It sounded like a simple question: “Will you fly the plane through Brazil to West Africa?”

Alas, in ferry flying, nothing is as simple as it seems. The business exists in a nether world between buyers and sellers, between the FAA in Oklahoma City and the aviation authority in every other country that has one. The seller want to hand the plane over and wash his hands of that particular deal (while keeping the customer happy) so he can move on to the next thing. The buyer wants a problem-free aircraft delivered to his home base as fast as humanly possible and at minimal cost (so he can keep it, and his business, airborne).

Whether new or used, acquiring an aircraft is an expensive, complicated, and often painful process–as anyone who has bought a plane, or a house, or a business can attest. A third party that can represent the buyer, negotiate with the seller, streamline the deal and get to closing makes life easier for both parties.

Enter the broker. The broker wants the buyer and the seller to come back the next time there’s a deal on the table–the way a restaurant wants you to come back when you’re hungry and you don’t feel like cooking (to enjoy consistently good meals and service at a reasonable price). The broker’s expertise and experience bridge the gap where the other parties either don’t want, or don’t know how, to tread.

But not all the bases are covered. Between the seller, the buyer, and the broker, somehow the plane has to actually get to the destination. If the buyer doesn’t hire a delivery specialist, the odds of a quick and cost effective delivery go way down. That’s where the ferry company comes in, covering territory where no one else wants to go. At the very end of the line, the ferry pilot carries the weight of every party’s combined efforts in a few days of intense, and sometimes dangerous, flying.

It’s a unique responsibility, and the pressure is on to get the job done. Inevitably opportunities to “do whatever it takes” crop up, and I often think the real art of the job is knowing where to draw the line. Aviation is filled with corner-cutters, and the temptation is there to be a hero and save everybody a bundle of time and money. But the consequence, at the least, is a bad reputation. At worst, you’re dead.

Back in 2012 I was faced with some decisions that should have been no brainers, but it took me a few minutes to realize that. I heard through the grapevine that a company I worked with (the Broker) had a customer (the Buyer) who needed some advice, and that I could expect a phone call. The Broker called me right away to explain the situation.

The Broker had done his part, and the Customer was the proud owner of a previously-owned King Air 350. The Customer had flown such planes from North America to Europe and Africa, and said he was confident taking this one along that route to his home country, Zambia. His problem was that Europe was refusing entry of this Zambian-registered aircraft. Would I talk to the Customer about how to get his plane home? “Of course,” I said, and took his number.

The Customer answered immediately. He spoke with the refined Central African White dialect, a blend of the Queen’s English and South African English. He was wondering if 1) I knew how to get permission from Europe, 2) if the route from Brazil to West Africa would be feasible, and 3) could we install a ferry tank if he wanted that?

The Customer had already flown to Bangor (a typical jumping-off point for North Atlantic crossings), was very eager to get across the Atlantic, and was understandably frustrated with the impediments to his progress. Get-Home-Itis was sinking in, and he was ready to do whatever it took, or to hire somebody who could do whatever it took.

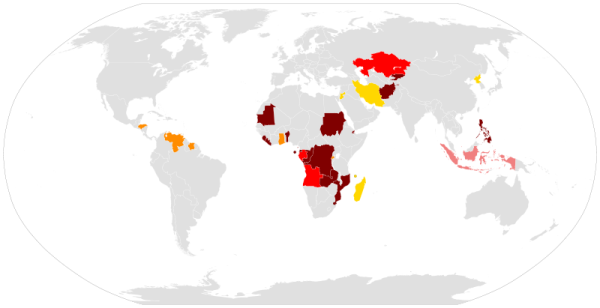

I had to research why Zambian registered aircraft are prohibited from EU airspace, and found that even the Zambian president’s presidential jet is banned, and that if he wants to go to Europe he flies British Airways. Their standards for airworthiness and regulatory compliance are so bad that Zambia is in the group of countries, depicted by dark brown below, whose aircraft are not just restricted to some degree, but banned entirely.

Having lived in Zambia, this was no big surprise to me. The surprise was that the Customer did not know this, and did not find out until he was already on the way home. Universal Weather & Aviation was handling the Customer’s trip planning and clearances. If anyone in Houston was aware of the prohibition, they were not the individuals doing the handling. Because they only broke the bad news when the Customer had completed the first leg of the ferry. Considering the week usually needed to obtain the airspace waiver for the U.S., I was doubly surprised this whole 350 project made it to the ferry without anyone knowing of the EU roadblock. But then again, they didn’t hire a delivery specialist …

So there would be no getting permission for the 9J registered plane to enter EU airspace. That’s a bigger issue that was way over my head.

“What registry did the plane come off of?” I asked.

“November.”

“Why not re-register? If it just came off November registry, and has only flown eight hours since, your DAR might take it back without an inspection,” I suggested. “Especially if you explain the circumstances, they will be willing to work with you on this. It doesn’t change the airplane one bit, but in the bureaucracy of Eurocontrol it would be a different plane, and you could be on your way.”

“Not an option” said the Customer. “If you knew the devil of a time I had getting the Zambian DCA to register it in the first place … they won’t just deregister. It will take a month, if they even agree to it. I want to explore taking the Southern Route.”

So we looked at the winds at FL300 between Fortaleza (SBFZ) and Sal (GVAC), the shortest leg down there that I had done. Light and squirrelly, with a short section of 20-knot headwind. At 1550 NM it might be doable.

“Get right up to three five oh and pull it back,” I said.

It’s amazing how a turbine can manufacture its own fuel. He didn’t want to go to Sierra Leone or Liberia, the closest points of approach.

“Are you RVSM?” I asked.

“No.” said The Customer.

He knew he wasn’t going to get a clearance eastbound above FL270, unless he lied about being RVSM. I explained how Brazil often requires paperwork in advance–aircraft docs, insurance, pilot certificates with type ratings, a visa in the passport–a whole other can of worms that might take days and days. It’s unlikely you could just say you’re RVSM and have them buy it. They can just look you up in the registry. That’s how a guy I heard of got busted delivering a CJ overseas above FL290. That cost him a 180-day suspension.

In a Zambian-registered plane between South America and West Africa, the repercussions of getting caught after the fact might be no worse than a letter from somebody’s Civil Aviation Authority, copied to the Zambian DCA. Of course monkey business like this is part of the reason he was in this fix in the first place: the EU doesn’t trust that any Zambian plane or pilot is safe enough to admit. Brazil might identify the pilot, so the next time he wanted to go there they would deny permission. But typically countries remember the aircraft instead–because an aircraft registration and operator is a lot easier to keep track of on a blacklist than a pilot, and the plane is probably never going back anyway.

“Another option,” I said. “You could file two seven zero, climb into RVSM airspace leaving Brazil, going point to point over the ocean off airway, transponder on On, not Alt, flight level three five five. Dakar wouldn’t catch it and Brazil is not likely to. It’s a big ocean, and traffic conflicts are highly unlikely.”

“What about going the other way?” he asked. “Across the Pacific?”

“Doable, but Russia and Japan are expensive and time consuming to deal with. From the Aleutians to Midway is another leg distance comparable to what you’re already looking at, and I need to see if Midway is currently open to private traffic. And the overall flight distance to southern Africa is double.”

We abandoned that idea.

“Now what about a ferry tank?” he asked. “A hundred gallons, or better yet a hundred and fifty, would make all the difference.”

I said I was sure we could install a 200-gallon tank. There wouldn’t be any paperwork on the tank job, because the FAA has no jurisdiction over foreign-registered planes. The Zambian system is based on the British system, and they don’t approve auxiliary fuel systems the same way the FAA does. To approve a tank job in Africa is more like getting an STC, not a field approval and a ferry permit. Getting approval in Zambia would be possible, though expensive and time consuming. Getting approval from the Zambian Director of Civil Aviation while in the U.S. really would not happen.

“Brazil has never asked me for tanking paperwork, and Senegal won’t bother. Just de-tank in West Africa and you’re home free,” I suggested.

The Customer said he had a stop where friends could do that. I said I would see about the tanking.

“I know you think re-registering borders on the impossible here,” I said, “but that really is your best option for remaining legal and keeping your insurance valid. It’ll take some time, but I really think you need to exhaust that option. Once you’ve totally ruled that out it’s time to seriously think about the other options.”

“Well, that’s not going to happen,” he replied.

“But you need to try.”

“Thanks,” he said. “I think Fortaleza to Sal at two seven zero will work.” And we hung up.

I called Mike the Mechanic and asked him when he had last tanked a King Air. It had been a couple of years, he told me, but he still had the paperwork. He could do it.

Tanking a King Air is more complicated than tanking a Caravan because the standard method of getting the fuel from the pressurized cabin to the wing tank is done through steel-sleeved hose that goes outside under the belly to the wing root. In flight there’s a ton of force pushing that hose, and it has to be bombproof. And you can’t just vent the tanks to the outside like in a non-pressurized plane. The vents have to be specially valved. The approved means of moving the fuel is with pumps, though I’ve heard of using the cabin pressurization to push the fuel–a method called “Blow and Go”. You just open the filler caps on the ferry tanks in flight. But without pressurization there’s no fuel transfer. Screw up any of it, and you might not get the fuel to the engines, or the tanks might collapse in the descent, or they might collapse from a pump-induced vacuum.

I told Mike to expect a call from the Customer about tanking the 350.

I often point out that the most difficult part of any ferry trip is the first takeoff. After weeks or months of ironing out issues with banks in Nepal, Airworthiness people in South Africa, and Airspace people in China, you finally get going and the plane is delivered in a few days. This Zambia scenario was one of those avoidable circumstances that should have been seen way back up the road. Now the Customer was all ready to go home, but the new delay was changing the way he thinks.

The next day the Broker called me back and asked the seemingly simple question we started this tale with: “Will you fly the plane through Brazil to West Africa?”

He continued. “The Customer knows you have to take the plane to three five oh in RVSM airspace. He’s willing to go if you’ll plan the trip and fly the plane. The ferry company doesn’t want to do the tank job.”

Mike the Mechanic’s boss didn’t want to touch this one, for some reason, and I had forgotten about my other friends in Kansas who have tanked a hundred King Airs.

“The Customer said that at two seven oh they’ll have ten minutes reserve at Sal,” the Broker said. “But at three five oh they’ll have forty five minutes. He’s comfortable with that.”

The day before, Sal was viable at FL270. Now it wasn’t. I didn’t have a 350 POH, so I was depending on the Customer until I got my hands on one. The Customer was ready to go Oceanic with 45 minutes reserve, based on book performance, because he had not taken the plane to FL350 to see what kind of performance the plane would actually deliver.

“Let me think about it,” I said. Immediately I knew what my answer would be, and felt silly for entertaining the idea even for a moment. Which means I really did need to think about it, to understand where I really stood, and who I really was.

“Does the plane have an HF?” I asked. “Does the Customer have a sat phone?”

“No,” the Broker said.

The nail in the coffin. With no long range radio or phone, no way to communicate to shore when beyond VHF range, we would have to lie about that and depend on relays with other traffic for position reporting to ATC if there was any other traffic within a couple hundred miles of wherever we happened to be. If we wanted long range comms I would have to install a temporary HF radio. No big deal, we could rent or borrow one. But it might entail drilling a hole in the plane, and it was just one more thing that had not been considered.

The nature of the whole dilemma was now crystal clear. You pick away at your options, you reduce your choices one by one until there is only one way to get it done, and you are only one hiccup away from an emergency of your own manufacture.

Flying can be challenging enough. Throw in some long range, and the chance of some bad weather, and you’re always carefully considering your options and whether to go.

Then …

… shave away a prudent, and legal, fuel reserve to change the destination to the only landing possible, with no viable alternate (there are a couple of other fields in the Cape Verde Islands, but with no fuel and no customs). Un-forecast adverse winds are common enough. You have to pad your reserve above legal minimums all the time to keep the pucker factor low.

… isolate yourself by eliminating the ability to communicate directly with oceanic ATC. Losing HF happens. Making them “talk” can be an art, and ferry pilots have to deal with that. But it gets quiet and lonely fast without your HF.

… launch on an oceanic leg depending on getting the plane to altitude immediately, and that it will perform as advertised without having demonstrated that performance before.

… on top of all this dodgy stretching, depart the U.S. knowing you’re depending on going oceanic in airspace where you’re not supposed to be because the plane and the pilot are not certified for it, so it must be kept a secret.

The Customer would be the PIC, and would bear all the legal responsibility. The chances of getting caught were slim indeed, and nearly impossible to prove. All the heat of the very remote chance of an investigation would be directed to Zambia, and the FAA would never hear word one. My ass was covered. I would get paid, and the Customer would be home free.

“No,” I said. “That’s not my style. The Customer says he won’t re-register the plane. I’ve described another way it can be done, but it’s not the way I operate.”

I realized something that made my choice clear.

“If we were already halfway there,” I said, “if there were really no other options because circumstances changed after we left the States, I could justify entertaining this plan. It can be done, but nothing can go wrong. This plan is clearly in the realm of last resort, and right now it’s really not our last resort. This airplane is still in the U.S., where we have the most options. The Customer currently has the most options he will have. The further we get down the road the fewer our options will be. Over the ocean there will be no options.

“If I were to accept your offer, I would be saying ‘This is the kind of person I am.’ And this is not the kind of person I am. I’ve flown your airplanes for fifteen years, and I want you to call me back for years to come. I want you to understand who I am and how I operate. If you take some time to think about it, you’ll realize that anyone willing to do this is someone who’s willing to put it all on the line for a little money. The sort of person you wouldn’t want to do business with again.”

I’m not a preachy, sanctimonious person. But I felt like I needed to describe why, after suggesting a course of action, I was not willing to execute the delivery as I proposed. A prudent businessman might describe why he’s said “yes” or “no.” But rarely will someone show their cards so candidly.

Regs get bent every day: going over gross, continuing with inoperative equipment. And then there’s my favorite Alaskan axiom which states: “If it’s too low to go VFR, you go IFR. If it’s too low to go IFR, you go VFR.” But to begin a seven-thousand-mile trip with a whole planeload of disadvantages really would be stupid. There had to be a better way.

“No thanks,” I said. “Good luck on this one.”

The next day the Customer called me to say he had persuaded the Zambian DCA to de-register the King Air, and the FAA had agreed to re-register it. The whole process would take less than a week, and would cost him less than tanking the plane and my fee. He’d head home safely with fat fuel reserves, his insurance uncompromised, and everyone’s reputation intact.

Contributing writer Alex Haynes (whom we interviewed in 2011) started his career flying in Zambia, then moved into ferry flying and a cush gig flying an amphib Caravan off the back of a royal yacht. He managed all that while raising a family. He lives in Seattle and ferries planes all over the world.

King Air 350 photo is a derivative of the color photo by Lord of the Wings licensed under Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 2.0 Generic.

Couldn’t you put the old N… markings over the Zambian numbers and take them off in Zambia?

You bet. And the registration, airworthiness, and insurance would all be false. Works great if nothing goes wrong. The old slippery slope.

I ferried Sundstrand Data Control’s Beech A65 Queen Air from Everett WA to Europe for VLA and Ground Prox sales demos to European airlines and government reps. All I had was VOR, DME, ADF – VHF comm only. Had to relay position reports via 121.5 and friendly PAA aircrews.

Mostly DR , but could use the Stavanger CONSOLAN for speed lines from Reykjavik to Shannon. September 1972 – lots of changes since then !!

Those were the days when being a ferry pilot was more lucrative and a lot more adventurous, when the generation that taught me built their experience. ATC on the North Atlantic still allows us to go with inop long range comms, if they determine there is adequate coverage for relays through other traffic. You can’t bank on it, so those who don’t have a sat phone or HF say they have one before leaving VHF, then BS their way over. But it gets lonely when you can’t raise anyone on VHF, especially at two in the morning when the temporary HF antenna breaks off in ice in the middle of that cold front…….